***

in memory of Stuart Raleigh

QUEER PIANOS FOUR HANDS

Drama, Camp, and the Gay Art of the Piano Duo

by Brian Taylor

***

From the salons of 19th-century Paris to mid-20th-century New York, the piano has provided a gathering place. Two oriented at one piano, or “piano four hands:” a place of creative and personal exploration, of discourse and celebration for generations. More extravagant yet equally intricate: the piano duo — “two pianos, four hands” — a phenomenon through which composers and performers identifiable as ‘queer’ revealed hidden lives in some of their most personal, queer-coded, yet often nostalgic and traditionalist, chamber music.

Benjamin Britten, Francis Poulenc, Samuel Barber, his partner Gian Carlo Menotti, their protégé Ned Rorem (and Aaron Copland, and Virgil Thompson…) were not only “friends of Dorothy,” but members of another club, as well. Rather than following prevailing compositional trends — serialism, avant-garde experimentation — they cloaked their musical voices in traditional, respectable garb, like an afternoon dance party in the guise of Afternoon Tea.

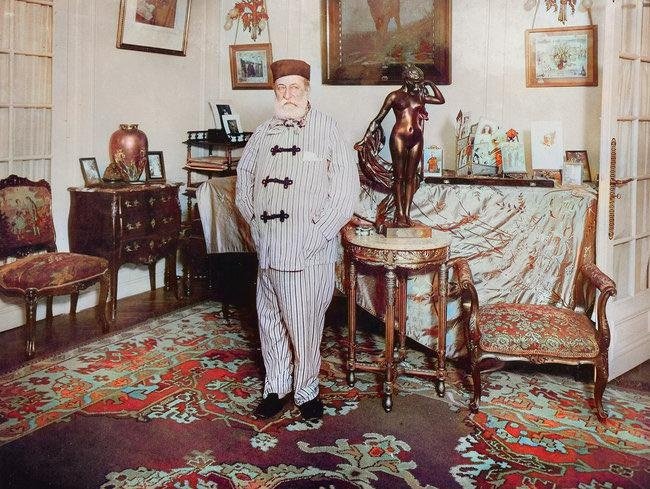

There’s a conservatism to the work of many gay composers of this era. Celebrated French composer and organist Camille Saint-Saëns was a staunch classicist in the shifting times of the late nineteenth century — lamenting Wagner’s influence and publicly feuding with the modernist Debussy — and was quoted rejecting the newfangled term ‘homosexuel,’ preferring the antique slang ‘pédéraste.’

In 1875 Moscow, Saint-Saëns met Pyotr Tchaikovsky, whose brother Modest recalled, “It turned out that the two new friends had many likes and dislikes in common, both in the sphere of music and in the other arts, too. In particular, not only had they both been enthusiastic about ballet in their youth, but they were also able to pull off splendid imitations of ballerinas. And so on one occasion at the Conservatory, seeking to flaunt their artistry before one another, they performed a whole short ballet on the stage of the Conservatory's auditorium: Galatea and Pygmalion.”

Saint-Saëns brought “exceptional conscientiousness” to the role of the statue, Galatea. It was not his first time in drag. Ten years earlier in Paris, at one of Emmanuel Chabrier’s musical soirées, Saint-Saëns sang and acted the part of Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust “with passionate ardour,” wrote Hughes Imbert. Saint-Saëns’ life, like Tchaikovsky’s, was marked by the tensions of public and private expectation.

Raised by two widows — his great-aunt Charlotte, and his mother Clémence (who oppressively disapproved of all potential girlfriends yet desperately yearned for grandchildren) — 40-year-old Camille still lived at home when he surprisingly married 19-year-old Marie-Laure Truffot. Arthur Dandelot (in La Vie et l’Oeuvre de Saint-Saëns, 1930) explained: Saint-Saëns was bathing at the école de natation Deligny on the shore of the Seine — which had a reputation as a homosexual gathering place — when a friend who knew that he wished to get married “put forward the claims of his own sister. Some time later, after the acquaintance was made, marriage was agreed and accomplished the following month.”

They had two sons, but in 1878, 2-year-old André fell out of a window and died. Six weeks later, the couple’s 6-month-old baby, Jean-François, died of pneumonia. The couple quickly estranged, and in 1881 the composer escaped on holiday, never to return nor see his wife again. In December, 1888, Saint-Saëns's mother died of pneumonia while he was embroiled in disputes readying the premiere of Ascanio at the Opéra. Plunged into suicidal depression and insomnia, within a year he had donated all of his belongings to the city of Dieppe, and embarked for Andalusia, “a night feeling in his mind.”

In Cádiz, he composed the only musical work from this period, 1889’s Scherzo for Two Pianos, Op. 87. He wrote of the piece in a letter, "I am at the mercy of the unexpected; I had no intention whatsoever of writing a scherzo…There are some oddities…Sight-reading it must be fairly painful; it is a piece one should not play until it has been mastered.”

He had written piano duos before — Variations on a Theme of Beethoven, Op. 35, and Polonaise in F Minor, Op. 77, among others. But the idiosyncratic Scherzo delves into the modernist color of his philosophical nemesis Debussy — whole-tone scales. Perhaps this iconoclastic harmonic palette reflected his emotional state. Another interpretation, given his views on such unorthodoxy: a combination of melodrama and satire. Camp, perhaps.

Saint-Saëns began traveling in the guise of “Charles Sannois,” merchant, leading a nomadic existence accompanied by his loyal manservant, Gabriel Geslin, visiting exotic locales like North Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America. The composer became a frequent resident of Algiers — the Palm Springs or Puerto Vallarta of its day (“You board a beautiful ship in Marseille and 24 hours later you land in Algiers; and it is sun, greenery, flowers, life!") — where he died on December 16, 1921 at the Hôtel de l'Oasis. Enormously famous in his home country, he was given a state funeral at Église de la Madeleine, where he had served as organist for 20 years.

*

In 1939 Britain, war loomed. Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears registered as Conscientious Objectors and sailed to America. They rented a room in a five-story house near the Brooklyn Bridge known as “February House” (eventually felled for the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway) where W. H. Auden was innkeeper to a rotating cast of characters, among them Gypsy Rose Lee.

Their friends in America included Scottish married piano duo Ethel Bartlett and Rae Robertson, who were described by the Boston Transcript as “the best beloved piano duettists in the world.” The Florida Flambeau wrote that Bartlett (who had studied with Artur Schnabel) was “known as one of England’s most beautiful women.”

Bartlett and Robertson premiered Britten’s Introduction and Rondo alla Burlesca, Op. 23, No. 1, at New York’s Town Hall in January 1941 (alongside Darius Milhaud’s Scaramouche). The New York Times described Britten’s Rondo as “interesting” and reminiscent of Hindemith; the Musical Courier called it “adroit and effective.” The Herald Tribune, however, found it “labored and ineffectual.”

Britten’s autograph manuscript for the Introduction and Rondo alla Burlesca.

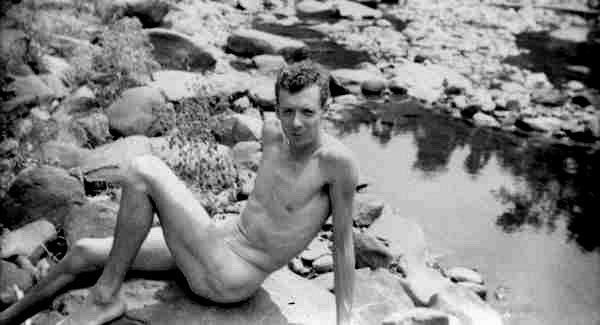

By June '41, Britten was ready to leave the city, writing in a letter that “New York is the worst, a struggling mass of scheming, shallow sophisticates & the lowest kind of every race under the Sun.” The Robertsons invited Britten and Pears to spend the summer of '41 in Escondito, California. Britten and Pears drove a borrowed old Ford across the continent, picking up hitchhikers and breaking down in the desert along the way. Once at the Robertsons’ house, they spent their days working — Britten with several commissions to fulfill, including Mazurka Elegiaca, Op. 23, No. 2, and Scottish Ballad, Op. 26, for two pianos and orchestra, for Ethel and Rae — and driving to the beach in the afternoon to get “sunburnt” and “drown our sorrows in the big waves.”

But, “an awful lot of energy is wasted in unnecessary emotional scenes,” as Britten put it in a letter to Elizabeth Mayer (July ‘41): Ethel fell in love with him, and Rae offered to relinquish his claim to his wife and ‘give’ her to Britten. It seems Britten and Pears were not ‘out’ to their friends.

The pitfalls of communication via telegram: Britten’s publisher Ralph Hawkes wired a request for a ‘two piano piece’ when he actually meant two pieces for piano, resulting in the Mazurka Elegiaca for two pianos. The occasion was Boosey & Hawkes’s Homage to Paderewski , an album of piano pieces by 17 composers, commissioned in 1941 in honour of the Polish pianist and statesman Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Britten’s duo (since it did not fit the overall project) was published separately but is still considered part of the overall homage.

A critic wrote of the mazurka, “There are no notes to spare in Mr. Britten’s music. The three sections of this somber Mazurka make their appeal bluntly and boldly and show the composer’s remarkable capacity for judging just how his score is going to tell in the concert hall. He has no use for elaborate detail nor does he burden the performer with technicalities, which the listener can seldom be expected to grasp.”

That “unhappy summer of 1941,” in a “marvelous rare book shop” in Los Angeles, Britten “came across a copy of the Poetical Works of George Crabbe” — his first encounter with the poem Peter Grimes, inspiring the first of his many operas often interpreted as dealing with repressed homosexuality, loss of innocence, and the plight of society’s outcasts.

Britten wrote home, “At the moment my greatest wish is to write as much as I possibly can, while I am still able & allowed to - because one never knows how long it will last, & I have such a hell of a lot I want to say.”

Britten and Pears returned to an England that criminalized homosexuality; although they never spoke about it publicly before Britten’s death in 1976, their relationship was an open secret during their 39 years together. Nonetheless, Britten became the first musician to be given a life peerage, taking the title Lord Britten of Aldeburgh. A similar American partnership also straddled public adulation and open secret: Samuel Barber and Gian Carlo Menotti, who met as composition students at Curtis Institute.

*

In the autumn of ’41, 19-year old poet Robert Horan, having hitchhiked across the country with his friend Pauline Kael (future film critic for The New Yorker), was hanging out in Grand Central Station when he encountered Barber and Menotti en route home from the opera and was invited to their Upper East Side apartment. He stayed: they formed a ménage à trois for the ensuing decade.

Horan served as Menotti’s secretary, and Barber set two of his poems to music, but by 1947 Horan wrote of “a very lengthy, and hopeless tension,” and “the emotional strain of the three-way relationship and the fascinating but rather high-powered personalities in their social world, made life perhaps not quite so serene as it seemed for a highly nervous and very young man.” Menotti summed it up best: “It soon became obvious that the apparent success of our triumvirate was illusory.”

Indeed, Barber and Menotti hovered in the highest echelon of American society — Arturo Toscanini and Vladimir Horowitz championed Barber’s music; the Metropolitan Opera commissioned Barber and (librettist) Menotti’s Pulitzer Prize-winning opera Vanessa; Jackie Kennedy was a friend — but their relationship was complicated. (Assuredly, they remained loyal to each other to the end — Menotti was present when Barber “died practically in my arms.”)

Francis Rizzo, assistant to Menotti, remembered “the improvident Gian Carlo would drink champagne, eat caviar, and run around all over the world. Sam would be stuck with the taxes, the phone bills, the servants — everything!” For himself, Menotti confessed “I just couldn’t live up to what he wanted me to be…I destroyed many of his illusions about me. You see, Sam is very much of a puritan, and he has no interest in petty things, while I have the soul of a concierge.”

In 1950, Menotti had taken up with the conductor Thomas Schippers (whom he met when Schippers accompanied an audition for The Consul — the singer didn’t get the gig, but the accompanist was quickly engaged to conduct the premiere). The same year, Barber was introduced to violinist and composer Charles Turner by Gore Vidal.

Ned Rorem, who had studied with Menotti at Curtis, wrote of Turner: “Chuck emanated neither narcissism nor ferocity, preferring the role of courtier to courted, and speaking quietly of all things cultured … I thought of him always as handsome, green, unpretentious, smart, more than presentable, a mensch.” Turner played the solo part in Barber’s Violin Concerto under the composer’s baton in Germany 1951 (Pierre Boulez, another legendary musical figure of speculative sexuality, was rehearsal pianist.) He had studied a summer with Nadia Boulanger, and became Barber’s sole pupil of composition. His 1954 Encounter was premiered by George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra.

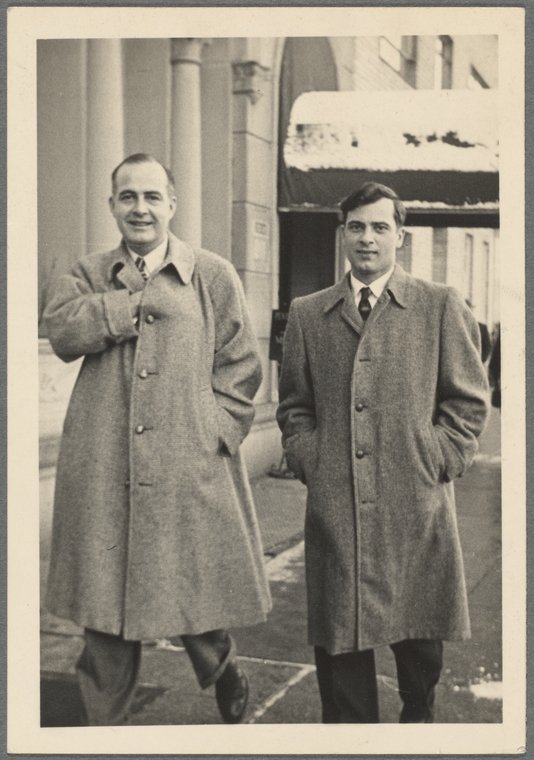

Samuel Barber and Charles Turner.

February 1952, Barber completed Souvenirs: Ballet Suite, Op. 28, a suite of six dances for piano duet for Turner and himself to play together, and to satisfy, as his longtime G. Schirmer editor Paul Wittke described it, his “gather-round-the piano side.” Turner had suggested something in the manner of Eadie & Rack — Eadie Griffith & Howard Godwin — who played showtunes on dueling pianos at the gay-friendly and desegregated Blue Angel Supper Club on E. 55th. Godwin had played piano for Judy Garland in “Easter Parade;” met Eadie in California and they married (she died in 1956).

Barber’s program note for his “ballet suite”: “One might imagine a divertissement in a setting reminiscent of the Palm Court of the Hotel Plaza in New York, the year about 1914, epoch of the first tangos; ‘Souvenirs’ — remembered with affection, not in irony or with tongue in the cheek, but in amused tenderness.” (The composer seems at pains to dispel the notion of deliberate camp, as Susan Sontag would have defined it.)

Robert Fizdale & Arthur Gold, pianistic and romantic partners, gave the official world premiere — in their own arrangement for two pianos (only slightly altered from Barber’s original) — in London’s Wigmore Hall, December ’52. The U.S. premiere was at the Museum of Modern Art, March ’53.

Barber, in a 1956 letter to Turner: “Much love, sacred and profane, and one very lascivious caress to make you shiver and sigh with deep desire: unsatisfiable…..except with me.”

Charles Turner, remembering Barber: “I think he thought of himself and his private life as a gentleman first of all, in that rather old-fashioned way that people had of being gay. I think it’s gone out of style now, maybe. But it never did with Sam. In fact I remember him saying to me not long before he died, ‘Well, who would ever know I was homosexual?’”

“I was supposed to be a doctor,” Barber told an interviewer in 1978. “I was supposed to go to Princeton. And everything I was supposed to do I didn’t.” His music was romantic and Italianate when abstract and austere was in vogue. Fellow queer composer Virgil Thompson implied that he was motivated by money: “A good businessman.”

*

Ned Rorem’s relationship with Barber was strained when Rorem shared (in his Paris Diary): “Sam Barber likes the story of a friend, who, seeking an uncontaminated native, went far away to the mountain village near the Swiss border. For reasons unnecessary to relate, he found himself in a sleeping bag with the blacksmith’s child. ‘Oh, I don’t mind,’ said the blacksmith’s child, ‘as long as you give me two hundred lira.’”

Meanwhile, Rorem spent the “very hot” summer of 1949 in Fez, Algiers, where he composed a “sizable Suite for Two Pianos for Fizdale & Gold — which they never played, nor has anyone else…”

Fizdale & Gold were classical music’s ambassadors to mid-century gay high society. As a piano duo, they were champions of new music, and tastemakers who shaped the repertoire. Rorem called them “the most important two-piano team that ever was, not only for their diamond-sure executions but for their causing major works to exist for their odd medium.”

In addition to being hot-ticket performers, Gold and Fizdale were legendary for their dinner parties. The “Fizgolds,” as some called them, defined artistic and gay cosmopolitan life in New York from the 1940s through the ’70s.

Thompson wrote of them, “Duo-pianism reached heights hitherto unknown to the art!” The New York Times: “Without doubt, this is the most interesting two-piano team in the business.” In the ’70s they began writing a cooking column for Vogue, and in ’84, published The Gold and Fizdale Cookbook: Food for Good Living.”

*

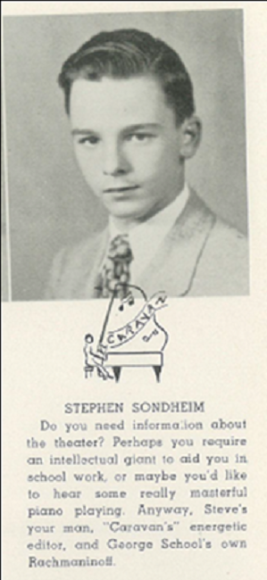

Stephen Sondheim was a precocious teen in 1940s Bucks County, PA, studying Chopin, Brahms, and Rachmaninoff on the piano. He later recalled playing Ravel’s Valses Nobles et Sentimentales “entirely for my own pleasure.” At age 16, he entered Williams College in the Berkshires under the tutelage of storied harmony professor Robert Barrows, former organist at the National Cathedral in D.C. and student of Ralph Vaughn Williams and Paul Hindemith.

In 1952, after studying with the post-Schönbergian maximalist Milton Babbitt, Sondheim composed Concertino for Two Pianos (at least, three of four intended movements) for his friend “Johnnie” Barry Ryan III — wealthy heir, arts patron, stage manager, and would-be producer — with whom he would make short horror films, and play Leonard Bernstein’s two-piano arrangement of Aaron Copland’s El Salón México on the two Steinway grands in the living room of the Midtown East apartment Ryan shared with wife D. D. (who would later design the costumes for Company). Sondheim referred to the first movement of the concertino as “Letters from Aaron Copland to Maurice Ravel.”

Sondheim’s artistic home, the theatre, often perceived his music as outré, but his French harmonic palette and Latin-American dance hall rhythms were rooted in German contrapuntalism. Meanwhile, in France, Francis Poulenc faithfully stuck to the melody-and-accompaniment texture of Neo-Classicism. For both Sondheim and Poulenc, pastiche, as in Barber’s Souvenirs, was a frequent springboard. Both Poulenc’s and Sondheim’s aesthetics blended high and low idioms (Poulenc’s pastiche never as sardonic as Sondheim’s), inhabiting a space between sincerity and irony.

Remembering Poulenc, Rorem wrote: “Who will forget that voice, spoken or sung? The harmless venom, the malignant charity? His indiscriminate choice of friends, yet so discriminately faithful to a type; la royauté des sergents de ville! I left a rare and fragrant package of Hindu joss-sticks (purchased the previous month near Tangier's Xoco Chico) with the concierge of Poulenc's Paris apartment. On returning to New York the following week, I found a letter from Francis thanking me for the incense, which he hoped would light the way toward one of les beaux flics that roamed his neighbourhood. The smoke, he said, weaved through his yellow plush armchairs, across the squeaking piano strings, and on out through the casements into the refracting sunlight of the Luxembourg Gardens…”

Poulenc began work on a sonata for two pianos in the autumn of 1952 in Marseille — staying in the same hotel room that housed Chopin on his 1839 return from Mallorca — and wrote of: “an apocalyptic suite for two pianos (Ah! Messiaen, where are you?) which is exhausting me with its noise and tension." Poulenc’s Sonate pour deux pianos, FP 156, was dedicated to Gold and Fizdale, whom he called “Les boys,” “with as much friendship as admiration.”

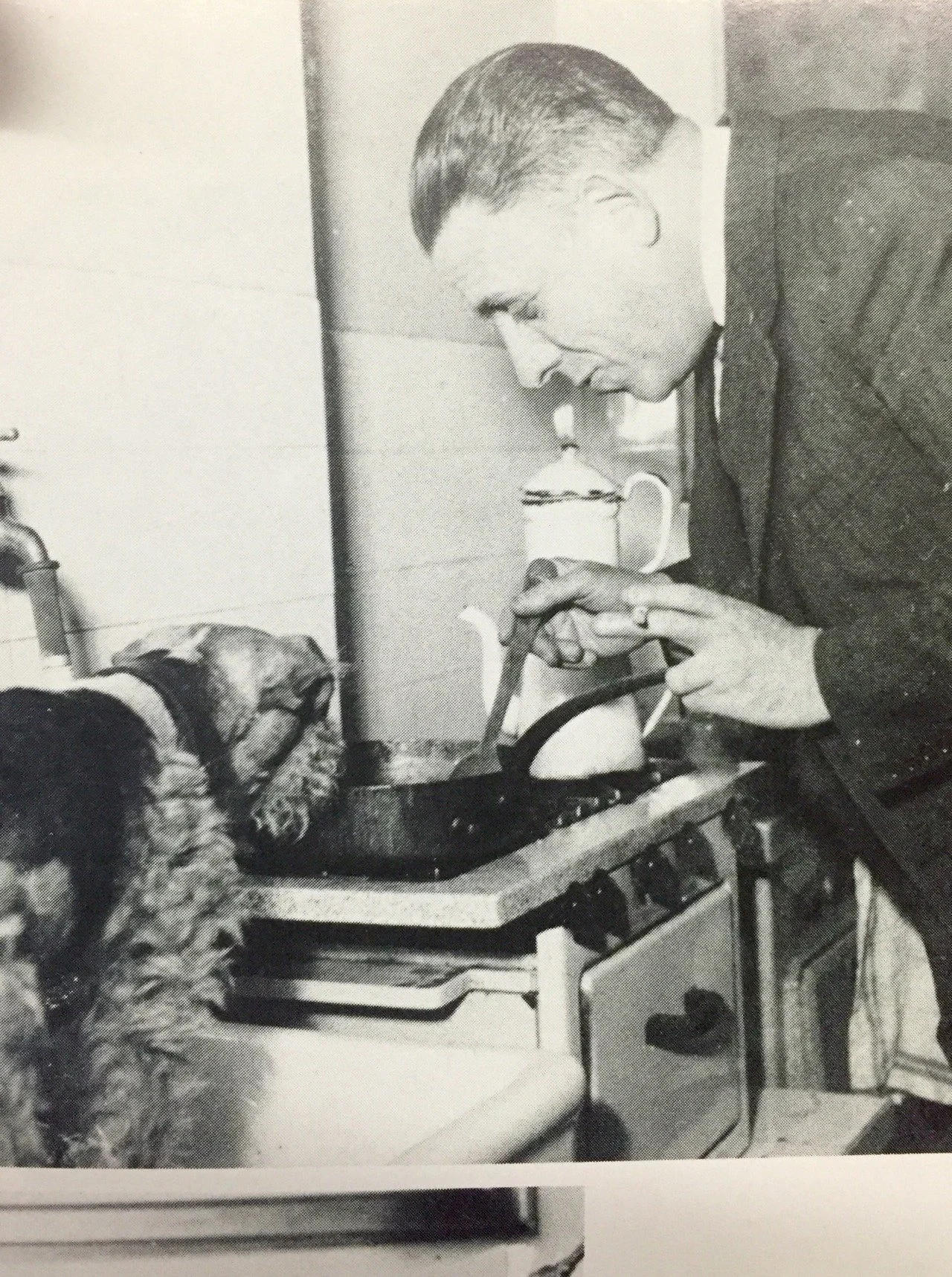

Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale

Poulenc said “the Sonate has the gravity of a string quartet,” and that the Andante third movement — inspired by his affection for Lucien Roubert, a married traveling salesman with whom he had a years long tumultuous affair — is “very spare. It’s piano writing without tricks, real piano writing in which each instrument converses in perfect agreement with its partner, without interrupting.”

Les Boys gave the sonata’s first performance in London’s Wigmore Hall in November, 1953.

*

This family of pieces is linked not only by its composers’ queer identities and the “odd medium” of two pianos, but how they embody what it meant to be queer in the twentieth century. Musicologists have sought “queer encoding” in these works — secret narratives, hidden Easter eggs — and identified common strains within fashionable cliques such as the Paris salon of the Princesse de Polignac, or the studio of Nadia Boulanger, whose gaggle of disciples like Copland, Thompson, and Rorem have been credited with creating a gay American sound.

Scholars have written extensively about the role of tonality and melody as markers of a distinctly gay modernist idiom in mid-century American music, and Britten’s “progressive conservatism.” More fascinating and meaningful is the psychology behind the music: the recurring theme of guilt, innocence, and transgression in Britten’s work (Leonard Bernstein called him “a man at odds with the world”), Poulenc’s fusing of cabaret superficiality with Catholic solemnity, and Barber’s frequent brand of elegy, longing, and melodramatic interiority. Tonality, lyricism, and traditional form (many dances) persist in this literature, but also narratives of internal conflict, tormented desire, and irony.

John Corigliano, torch bearer of his friend Barber’s neo-Romanticism, commissioned to contribute a piece for a two piano competition “couldn’t think of anything else I wanted to say in that medium. I couldn’t see what made a second piano so important. It was the same sound; it was simply a matter of adding another player. I couldn’t reconcile why I should write for two pianos when I could write as well for one.”

He supplied a fine piece for two pianos tuned a quarter-tone apart called Chiaroscuro, but was mistaken in his assessment of the potential in writing for a pair of pianos. If four hands on one keyboard is about artistic and physical togetherness — intimate fun — then two pianos, four hands becomes about something different.

Two pianists, each with their own full-fledged instrument, their own freedom to move about the entire range of octaves, their own pedals, dampers, and soundboards. Yet, intensely collaborative, requiring a language of cues (subtle gestures, breath), and solving problems of balance and voicing (the negotiation of dominant and supportive roles). The piano duo as metaphor was at its most elegant in the coupling of Gold and Fizdale, Les Boys, the Fizgolds.

At Gold and Fizdale’s behest, Poulenc wrote his final piano piece, Élégie (en accords alternés), FP 175, for two pianos, in remembrance of singer and arts patron Marie-Blanche de Polignac, niece by marriage to Princess Winnaretta Singer-Polignac, the dedicatee of Ravel’s Pavane pour une infante défunte, a formative sponsor of Poulenc’s, as well as much French music of the early twentieth century. (In 1932 the American-born princess had commissioned Poulenc’s Concerto for Two Pianos in D Minor, FP 61. )

Poulenc advised that the Élégie should be performed as if “improvising, a cigar between your lips and a glass of cognac on the piano.”

***

Bibliography

Britten, Benjamin. Letters From a Life: The Selected Letters and Diaries of Benjamin Britten. Volume One, 1923-1939. University of California Press, 1991.

Gold, Arthur and Robert Fizdale. Misia: The Life of Misia Sert. William Morrow & Company, 1981.

Gold, Arthur and Robert Fizdale. The Gold and Fizdale Cookbook. Random House, 1984.

Hubbs, Nadine. “Homophobia in Twentieth-Century Music: The Crucible of America’s Sound.” Daedalus, Vol. 142, Issue 4. 2013.

Ivry, Benjamin. Francis Poulenc. London: Phaidon, 1996.

Kildea, Paul. Benjamin Britten: A Life in the Twentieth Century. Penguin, 2013.

Laurents, Arthur. Original Story By: A Memoir of Broadway and Hollywood. Applause, 2000.

Nichols, Roger. Poulenc: A Biography. Yale University Press, 2020.

Pollack, Howard. Samuel Barber: His Life and Legacy. U. of Illinois Press, 2023.

Rees, Brian. Camille Saint-Saëns: A Life. Chatto & Windus, 1999.

Robinson, Suzanne. “An English Composer Sees America: Benjamin Britten and the American Press, 1939-42.” American Music, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Autumn, 1997).

Rorem, Ned. The Paris Diary. Braziller, 1966.

Rorem, Ned. The New York Diary. Braziller, 1967.

Rorem, Ned. Absolute Gift. Simon & Schuster, 1978.

Rorem, Ned. Knowing When to Stop: A Memoir. Simon & Schuster, 1994.

Secrest, Meryle. “The Mystery of Sondheim.” Airmail, Issue 233, 2023.

Secrest. Stephen Sondheim: A Life.” Knopf, 1998.

Southon, Nicolas, and Roger Nichols. Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart. Ashgate, 2014.

Swayne, Steve. How Sondheim Found His Sound.” U. of Michigan Press, 2005.

Swayne. “Sondheim’s Piano Sonata.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association, Vol. 127, No. 2. Taylor & Francis, Ltd., 2002.

Teachout, Terry. “Samuel Barber’s Revenge.” Commentary, April 1996.